In 2016, political pundits were stunned by the presidential election results. Donald J. Trump would be the next president of the United States, defying most political pundits’ predictions. This prompted the media, politicians and others to reflect on the accuracy and usefulness of election forecasting.

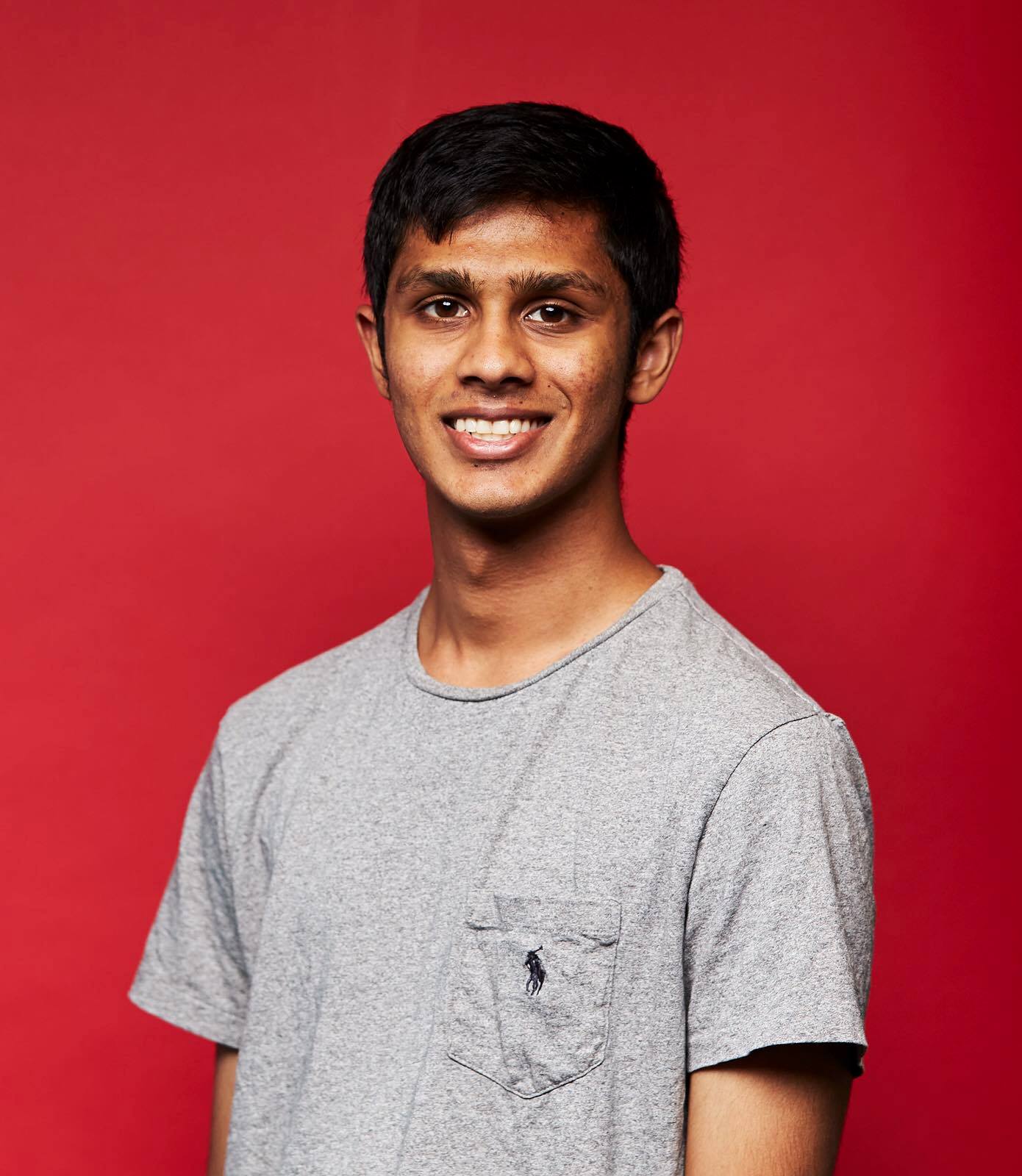

Heading into the 2024 presidential election cycle, we spoke with Lakshya Jain, an election forecaster and UC Berkeley computer science and engineering alum. Jain shared how computing has changed political prediction efforts and why he started Split Ticket, a political analysis website. He also discussed how the August 23 Republican presidential primary debate fits into forecasts.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Q: What is election forecasting?

A: Election forecasting [is the process of examining] a whole bunch of data and underlying information about an election and make a prediction about what the result will be.

Q: How does computer science fit in?

A: A lot of the more recent advancements in election forecasting and analytics come from people trying to use data to predict what will happen in an election based on the underlying trends, for example, or the demographic profile and baseline partisanship of an area. [We consider] these [indicators] and try to make an inference about what the actual margin will be.

The way we do that – at least the way I do it and the way a lot of newer folks do it – is that we like to make models for it. We code up and create models that will take in [and process] data in large batches. The models essentially are trained on a bunch of past election results. You can then get a better understanding of how historic and recent profiles, demographics and different types of variables have correlated to election outcomes. Then you can take your data for this election and try to make a prediction off of that.

Q: How did you get into this field? What is Split Ticket, and why did you start it?

A: During the pandemic, I was really, really bored. When I started reading about the presidential election in 2020, I was seeing takes from people and I had no idea whether they were true or what they were based on.

I said, ‘Isn't it possible that they have some biases as well? Something that they might be missing?’ I was like, ‘Let me see if I can use my own background for it.’ My first attempt was not at all successful. I made the mistake of thinking that just because you know how to code means you're insulated from biases. That's not true. There's a lot of different ways bias and misunderstandings can creep into even a code-based approach to elections. That was a very instructive moment for me. I [knew] I had to have a more holistic understanding of [elections] and blend that more qualitative understanding with my hard quantitative skills.

I had a lot of fun with it. My friends and I were on Election Twitter. We decided instead of tweeting our opinions about politics, we’d start writing about it. That's what happened. [Today] Split Ticket is an elections forecasting site that is data driven and seeks to use electoral data to understand trends and elections, figure out why results happened the way they did and predict what results are going to happen in the future.

Q: Who is election forecasting for?

A: It's really for almost anyone. It’s for media and political professionals whose entire jobs and professions depend on this thing – who are actually running these elections and want to figure out where they're supposed to target votes and whatnot. Also – and I think most importantly – it's for the average everyday person who doesn't have the time to look at the profile and demographics in every state, every congressional district, every election and see who's favored.

"We thought there was still an opening for ways that you can use data to more accurately describe what was going on in the political landscape."

Q: Why should a regular person care about these predictions?

A: It's an interesting question. I've had people say, ‘Well, it's not like I can change much, so I'll just go and vote, and whoever wins, wins.’ I don't think it’s good to look at it like that. I think we should care about election forecasts because there are material differences that these elections make to the lives of people.

If you're an average consumer who's not too politically engaged, you still want to know who is more likely to win or not. The differences between the parties have not been this stark for a long time. Understanding who is more likely to win [signals] what the country seems to be feeling right now. It can help you understand what's going on in the nation and why, and you can apply it to your daily life.

Election forecasting is a way to drive civic engagement. When you're engaged in things like who’s going to win an election or not, there's a symbiotic effect with political engagement in general. You start paying more attention to news. You start paying more attention to events. You start holding people accountable.

Q: You said you started predicting elections in 2020. What prompted you to try it?

A: I have a lot of respect for people who have done this for a long time. It's said that the more data a model has, oftentimes the better it is. [People] who have done this for a long time, like John King or Larry Sabato, what's happened in their brains is essentially no different from training a model on a lot of data and seeing how it adapts and adjusts. But the average forecaster is not as good as those people are. Even if they may have been doing it for a while, they have a lot of biases that creep into their work. They’ve also had high-profile misses.

In 2008, people were treating [the election] as like a toss up. Nate Silver was like, ‘No, this is a slam dunk victory for [Barack] Obama. That's what the data says.’ And he was right. People started realizing that the conventional way of covering elections was badly broken and that a new data perspective was more important. I think the reason election forecasting has gotten a bad reputation is because people started misinterpreting what the data was saying and started having a false degree of confidence in some forecasts after the successes of 2008 and 2012.

The reason we founded Split Ticket was because – just like what Nate Silver saw in 2008 – we saw the way politics was being covered. We thought there was still an opening for ways that you can use data to more accurately describe what was going on in the political landscape. We look at the conventional wisdom people are saying and challenge it – see if it’s true or not. A lot of times it is. It's conventional wisdom for reason. But sometimes it's not. Sometimes we find that we're able to use our data-oriented lens to break long-held notions. That's a lot of why we do it.

Q: How do presidential debates fit into your models?

A: Frankly, debates don't actually play much of a role into election forecasting at all, at least they shouldn't. Empirically, we find that debates – in general elections at least – do not move the needle much at all. People increasingly have their mind made up. After a debate you'll see a brief polling bump based on who the electorate thinks won the debate, and then it fades away as people forget about it. If you start paying too much attention to who you think wins a debate, that's exactly how you land in the area of, ‘Oh, I think X is going to win’ based on nothing more than vibes when really the data doesn't support it.

For primary elections, there is an argument that debates do more because it's an opportunity for candidates to get more visibility and get more donations. That's important because donations are something that actually correlates with electoral success. I don't think this one will because Donald Trump is a front-runner far and away. Everyone else is just jockeying for second. Maybe you might see a little bit of movement, but honestly, I'm not expecting this upcoming debate to change anything regarding the odds of who gets the next nomination. I think that's still looking like it's going to be Donald Trump, unless for some reason he magically can't run anymore.

Q: What advice would you give to students about finding their own path and career in election forecasting?

A: There's a very low barrier to entry in elections forecasting. If you get started with even the smallest project, you'll find a whole new wave of opportunities available to you. Elections data forecasting is a very new field. There is a lot of low-hanging fruit that people can find if they want to get involved. I would strongly encourage people to get involved in it.

The other thing I would say is a lot of people tell me, ‘Oh, I have no political science experience. I care about it, but I don't have political science experience. I'm just a programmer.’ That's the same way I got started. You don't need political science experience to get started. You just need humility and a willingness to understand that as you get started, you will be wrong on a lot of things, and that's okay. Just be willing to understand that you'll have to challenge your ideas.