Nearly 70 years after the launch of the first satellite, we still have more questions than answers about space. But a team of Berkeley researchers is on a mission to change this with a proposal to build a fleet of low-cost, autonomous spacecraft, each weighing only 10 grams and propelled by nothing more than the pressure of solar radiation. These miniaturized solar sails could potentially visit thousands of near-Earth asteroids and comets, capturing high-resolution images and collecting samples.

Led by Kristofer Pister, professor of electrical engineering and computer sciences, the researchers seek to leverage advancements in micro-scale technology to make interplanetary space exploration more cost-effective and accessible — and to accelerate new discoveries about our inner solar system. They describe their work, the Berkeley Low-cost Interplanetary Solar Sail (BLISS) project, in a study published in the journal Acta Astronautica.

The BLISS project brings together researchers from the Department of Electrical Engineering and Computer Sciences and the Department of Mechanical Engineering, as well as the Berkeley Sensor and Actuator Center and the Space Sciences Laboratory. Their work builds on other small spacecraft projects, including CubeSats, ChipSats and the Breakthrough Starshot Initiative, while seeking to improve solar sail maneuverability and further reduce fabrication costs by using low-mass consumer electronics.

In addition to Pister, the team includes lead author and mechanical engineering doctoral student Alexander Alvara and co-authors Lydia Lee, Emmanuel Sin, Nathan Lambert and Andrew Westphal.

In a recent conversation, Pister and Alvara shared their group’s vision for this project with Berkeley Engineering.

Your latest paper focuses on fleets of small solar sails. What advantages do solar sails have over other types of spacecraft?

Alexander: Solar sails use a non-consumable propulsion force. They are propelled by sunlight, similar to how a sailboat is propelled by wind. So, unlike other spacecraft, solar sails can travel around the galaxy, or, more specifically, our solar system, without having to carry any fuel or worry about refueling.

Kris: The magic is that light, even though it doesn’t have mass, has momentum. When light bounces off a mirror, you get a force due to that change in momentum. And on a square meter sail, that force is tiny. It’s about the weight of a grain of sand, but you get it for free. And you get it for as long as you want, as long as you’re sitting in space with the sunlight striking you.

Could you tell us about the Berkeley Low-cost Interplanetary Solar Sail, or BLISS, project? What was the genesis of this project and what are its goals?

Kris: It started several years ago, when friends of mine were exchanging emails about an object, called Oumuamua, that was moving through our solar system. Some people were saying that maybe it’s an alien solar sail, and then [physicist] Dick Garwin sent around a paper that he had written in 1959 about solar sails. It said that you can use this light pressure to move out, away from the sun, which makes sense — the light pushes in that direction. But you can also use it to move in. It’s kind of like tacking against the wind in sailing. Light is much more like wind, and you can tack using solar radiation pressure.

So this lightbulb went off in my brain. All the work we do in my group is focused on miniaturizing things, and I thought we could miniaturize a solar sail spacecraft. Seeing that you can tack against light pressure made me realize that we could make spacecraft [weighing] 10 grams with almost all off-the-shelf technology. And our latest study provides evidence that this is feasible.

Our initial goal for the BLISS project was simple: capture images of all the near-Earth asteroids, starting with the biggest ones. Roughly a thousand near-Earth asteroids are bigger than a kilometer in diameter. And we have pictures, usually fuzzy pictures, of maybe 10 of them. We were excited by the idea that you could potentially take an iPhone camera, orbit around one of these things, take a thousand high-resolution color photographs from a very close distance and then beam that information down.

Speaking of miniaturizing things, why make the solar sails small in the first place?

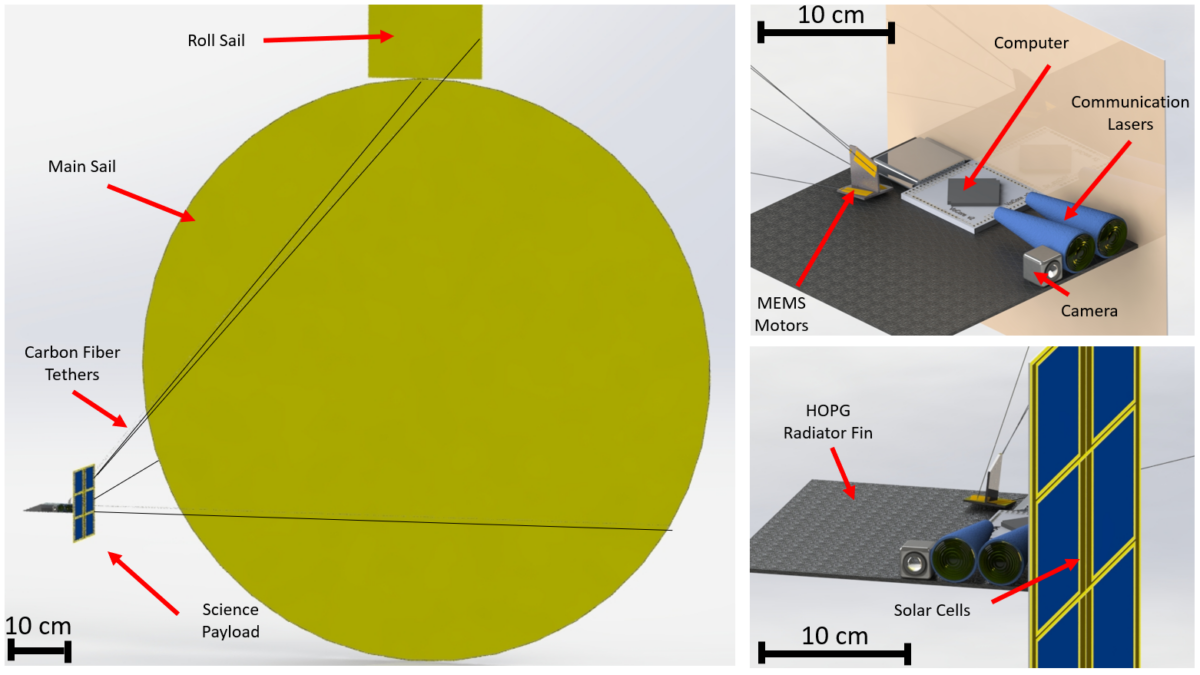

Alexander: A smaller size allows the spacecraft to be more agile. We don’t have to worry about buckling of the sail, which is just one square meter. This is a huge issue with larger solar sails. Imagine taking a solar sail that is 50 square meters into space, then having unfolding components spreading out like origami. It’s still relatively small compared to other spacecraft, but the unfolding components add weight. And, as Kris mentioned, you’re getting the force of a grain of sand continuously on your sail, the light pressure, so you want to have a solar sail close to that mass. You don’t want something that’s huge, or it will take forever to move, and it’s going to be less easy to maneuver.

Kris: Cost is another advantage to going small. We’re proposing to start at about 10 grams for an interplanetary spacecraft. If we do everything right, the cost of the solar sails will be a thousand dollars or less. We could then put thousands of these tiny spacecraft in a little package, the size of a small satellite, and launch them into space.

Alexander: So, for the cost of a single launch, we could send out thousands of these solar sails and accomplish multiple missions.

These spacecraft will need to be highly functional yet also light. How will they not be weighed down by all of their components?

Kris: We’re leveraging all the technology, all the miniaturization and low power consumption that goes into the design of cell phones. But there are also many other instruments that MEMS [microelectromechanical systems] has managed to miniaturize.

The BLISS spacecraft uses a MEMS device called an inchworm motor. What is an inchworm motor and why is it important?

Alexander: You can think of an inchworm motor as something that takes electricity and turns into a moveable force. Almost like a piston. We use the inchworm motor to grab onto things, in this case, things that are much larger than itself, and move it back and forth.

Kris: Our little spacecraft has roughly a 1/2 meter diameter, super-lightweight mirror — maybe the size of a card table – that is connected to the body of the spacecraft by a few carbon fiber filaments. The inchworms inch their way along those filaments, pulling on the filaments and moving the sail relative to the center of mass of the spacecraft. It turns out that’s what you need to navigate — just like on a sailboat. You pull on the lines and change the attitude of the sail through the wind, and that affects direction.

How will these spacecraft navigate the inner solar system?

Alexander: The majority of the analysis is done using something called the Lost in Space [Identification] Algorithm. The idea is that you map the stars that you can see, then compare them to the pixels of the images that you can get from your on-board cell phone camera. So we can basically use smartphones to help navigate.

There are many hazards in space, including ionizing radiation and large floating particles. How do you design the tiny solar sails to withstand these potential dangers?

Alexander: A lot of work has already been done analyzing off-the-shelf parts that have endured space-like radiation. To mitigate such hazards, we can either build in redundancy and add multiple components that have the greatest likelihood of failure, or pair these BLISS spacecraft in what we call partner constellations, which basically adds redundancy for us.

Could you tell us about the concept missions that you’ve proposed for BLISS spacecraft? How long would it take to complete these missions?

Alexander: Kris had mentioned earlier sending the solar sails to explore near-Earth asteroids. One of the other main concept missions is cometary sample retrieval, so getting microdust from comet plumes. To date, there’s been only one real successful return of cometary material, and that was the Stardust mission in the early 2000s. It did a flyby of a comet called Wild 2 and collected material and brought it back to Earth. But unfortunately, the spacecraft was less maneuverable than they expected, and it caught the comet dust particles at high velocity, vaporizing any organic-rich components in the sample. Though the sample they retrieved was still vastly important, we currently have only about 300 micrograms of comet material on Earth. And by designing our tiny solar sails to be agile and highly maneuverable, we hope to capture cometary samples at low relative speeds to avoid damaging any organics.

Kris: As for the mission durations, they vary a lot. It will take us some number of months to get out of Earth’s orbit, it will take us months or years to get to the asteroid or comet that we’re interested in, and then the reverse of that coming back in. So, certainly months at the short end, and maybe a decade or so at the long end.

How far off are we from the first launch?

Alexander: We could feasibly do it in a few years. For example, CubeSat projects usually come out of high schools or community college or four-year institutions, from undergrads. And those go from zero to launch in about two years. So with grad students, post-docs or research scientists on the job, who’ve been doing this sort of thing for many years, we should be able to launch within that same timeline once we complete development.

Kris: So far, Alexander’s worked on some of the theories and some of the motors. But there are six other systems and all kinds of software still needed, so it would be an undertaking. But I’m hopeful that we can obtain funding for further research.

This story was first published by UC Berkeley's College of Engineering.